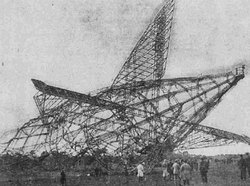

The R101 airship wreckage

The R101 airship wreckage The disaster is notable for the multitude of human factors that were present. Probably the most significant was the time pressures that the design and construction team faced. These resulted from a deadline imposed by the Air Ministry for the first flight - to India and back - to take place in September 1930. This was so that the Air Minister could arrive back in England, aboard an airship, for the Imperial Conference in October. The British government wanted to show off to the collected prime ministers of the Empire what it could do when put in charge of large industrial projects. Future airship development (and thousands of jobs) were dependent on meeting this deadline.

The whole design and construction was fraught with technical challenges; solving one problem created many new ones. The airship was heavy - the hydrogen gas was not sufficient to support the airship's weight. Significant efforts were made to lighten the airship, and an extra bay was inserted in the middle of the airship. This was a major operation - the airship had to be cut in two, a new section (11 metres long) inserted and the whole thing joined back together. This section contained an extra gasbag and gave the airship an extra 7 tonnes of lift. It also meant that the airframe would now be subject to different stresses and strains that had not been considered at the initial design stage. Lightening the airship meant that its viability as a commercial venture was likely to be doomed, as many of the luxury fittings had to be stripped out. Obviously this would not impress the passengers nor the high-ranking officials who would go aboard the airship in Egypt (a planned stop-off point on the journey) and India. So, despite concerns about weight, a 180-metre long Axminster carpet was fitted in the main corridor and another similar one fitted in the tennis court-sized main lounge. Given that a layer of dust an eighth of an inch thick across the top of the airship was said to weigh a ton, this extra load would have been significant. There was also a lot of heavy cargo - deemed essential for taking to Egypt and India as a showcase of British exports. This included casks of ale, cases of champagne and silverware. Concerns about weight were so severe that the crew had been told to leave their parachutes behind in the sheds at Cardington.

R101 at its mooring mast

R101 at its mooring mast On top of all this, the UK Air Ministry at the time, whose role it was to scrutinise and advise the airship design and construction team at Cardington, was made up of aeroplane experts. This meant that there was little effective impartial challenge to the work.

All the test flights had been carried out in perfect flying conditions, so the airship was virtually untested in poor weather. Today, these factors are more commonly known as 'safety culture'.

The size of R101 is hard to comprehend; it was nearly 237 metres long and 40.6 metres in diameter. It took 200 people to 'walk' the airship from its shed to the mooring mast (although 550 were used on the final movement, in case of blustery weather). The sheds at Cardington still exist, one as a film studio and the other as the home of the Airlander project. There is a website that gives the history of these enormous structures.

There are memorials at Cardington and in Beauvais, France.

Much has been written about the disaster, but James Leasor's excellent book is well worth a read.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed